My recent Substack piece “There’s Gonna be a War in Montana” did not, in fact, predict WWIII, but people still took it that way. Those who declare the end of history and/or those who call the prospect of war “beyond absurd”—as many who critiqued by piece did—refer to a war war sort of war, like the Civil War or WWII. They don’t mean that no political violence will occur, because it already occurs all the time. They mean that a Big War is very far down the road, if such a thing is even possible anymore.

But their naive protestations towards those of us who discuss war as a present possibility, whether big or little, reveal a disingenuous position. They mistake the bathwater for the baby. When I wrote “There’s Gonna be a War in Montana,” did I mean a four-year, proper-noun, one-million-dead war in Montana tomorrow, or next week, or even next year? Of course not. No serious person could think that. What I meant (besides the obvious commentary on not war but mainstream war discourse, which I won’t get into here) is “it looks like there’s going to be a confrontation in Montana, the beginnings of a much bigger and longer conflict, and here’s why.” It was simply to describe the new sides in a battle that not only will get hot, but already has. Self soothing with “war is beyond absurd!” is a cryonic fantasy for Godless milksops who’ve never truly left the womb.

In downtown Lawrence, Kansas, a college town to be fair, a bald man wearing black latex body armor, bicycle shorts, and a raccoon tail walks past the bookstore. It’s just the sort of quaint little book shop you’d imagine in Lawrence, with one noticeable difference. A printed sign blocks out one of the panes, no longer reserved for the pleasure of window shoppers strolling by. Warm yellows and browns, an all caps font that suggests handwriting. “MASKS REQUIRED - THANKS.” It’s September, 2022.

I had a client in Lawrence, so I spent a couple weeks driving around Kansas, Missouri, and Iowa. I saw a lot of the same signals I detailed in “There’s Gonna be a War in Montana,” which struck a chord, I believe, because it detailed the propaganda, aesthetics, and positioning of the sides in a relatively new conflict that will define the coming age for not just decades, but for centuries to come. Many Americans have noticed these signs and symbols in their own cities—the rainbow flag sticker on the door of that new loft building, an uptick in angry right wing bumper stickers just outside of town—which is why the piece resonated with so many people.

I saw my first Confederate flag in Clinton, Missouri, about 100 miles southeast of Lawrence. You can still feel the old dichotomy of Missouri, a former slave state, versus Kansas, which was not. Kansas gives friendly, rigid, puritan, flavorless—chicken fried steak, white gravy, side of mashed potatoes. Cross the state line and Missouri is instantly wilder, greener, more dilapidated; you’ve entered The South. Indeed, six years before the Civil War, pro-slavery “border ruffians” from Missouri clashed with “free staters” (including John Brown) from Kansas in a hot conflict—”a series of violent confrontations”—known as Bleeding Kansas. A couple hundred people died and the free-staters prevailed. But then the Civil War, the war war, began, resetting the conflict anew.

In semi-rural Missouri, forty minutes outside of St. Louis, I map to a random bar to soak in the milieu. A small but powerful Patriot Front sticker—“AMERICA FIRST - PATRIOT FRONT —is affixed to the screen door window, just above the handle. The screen slams behind me and inside a group of old men with Shenandoahs and leather jackets look up at me quizzically. Chugging Busch Light at the bar, I google Patriot Front—the first two results are ADL and SPLC blacklists, others call it “the most active white supremacist group in the nation,”—“They Are Racist; Some of them Have Guns.” Nobody gives me any grief as I sit and clack on my phone, but I roll out in a prudent amount of time, heading towards St. Louis.

St. Louis. One should not operate predatory SaaS while driving, and in doing so I accidentally booked an uncancellable reservation at a $300/night hotel ($350 after fees) in the center of downtown or, as I would soon learn, the bombed out and depleted whirlpool of chaos that used to be downtown St. Louis. Online, the hotel presented itself as a typical record-player-in-every-room industrial chic hipster spot, with your usual bespoke cocktail menu, boho art, and rooftop pool. I pulled up in front of the hotel where a short Italian valet informed me there were two options for parking, $30/night lot where my car would almost certainly be broken into you (they were of course not liable in such instances) or a “much more secure” $60/night lot with posted guards, where they could guarantee its safety. Inside, the overwhelming smell of mildew filled the cavernous foyer. Chipping paint. Dirty corners. Phony Basquiats hung slightly crooked on the walls. At the counter, the desk clerk holds her crying baby. Despite it being 5pm, the room isn’t ready, so I join the crowd of bewildered travelers at the bar, where I’m offered a free drink. I order a La Croix. The bartender hands the can over; dead moth wings adorn the rim.

In the room, the sound of rushing water shakes the walls every few minutes. But that’s the least of my worries—after dark, the streets transform into a all-night twerk party, screeching tires, thumping bass, and just flat out screaming. I give up at 6am and hightail it out of there, just in time to see a young man and woman smoking crack on the ledge of the lobby windows.

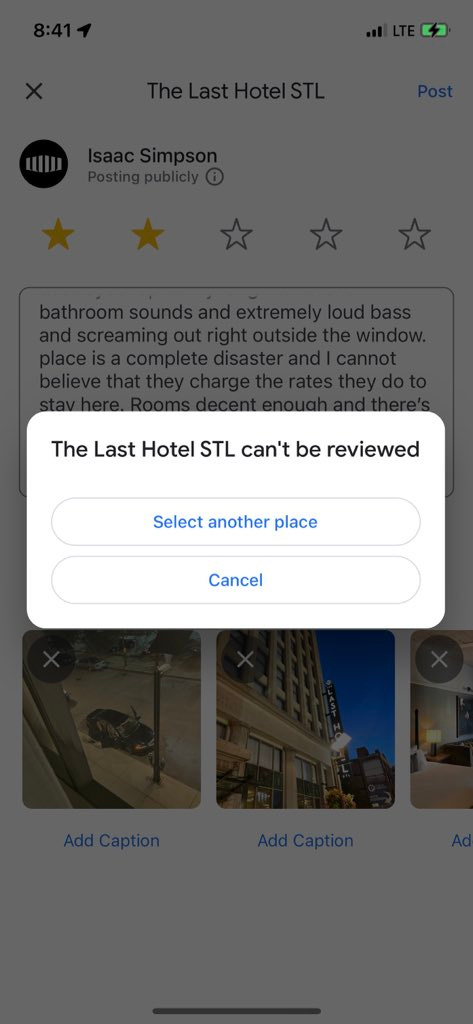

I go to write a review of this abomination—$350 a night!—to at least warn others off, and I learn that for some reason my reviewing privileges have been suspended, or at least I’m unable to review this location.

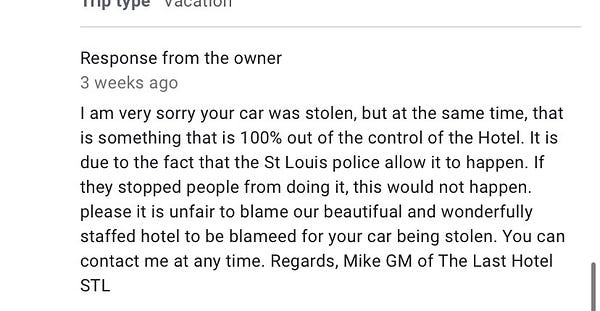

Reading existing Google reviews of the place provides a straight hour of laugh out loud entertainment, particularly when the manager blames guests for complaining about having their cars stolen.

I know that many will say, wow, big deal, you had a sh*tty hotel experience, and that somehow means there’s going to be war? Give me a break. This is of course not my point. What I’m trying to describe is what the new landscape of this country looks like, how territory is used and occupied, and by whom. To draw lines on the map and to articulate the symbols, principles, and methods of the groups on each side of them. To help people understand that in many ways, the coming conflict isn’t coming anymore; it’s already here. For the Patriot Front members at that bar, at least, St. Louis is in every sense occupied territory.

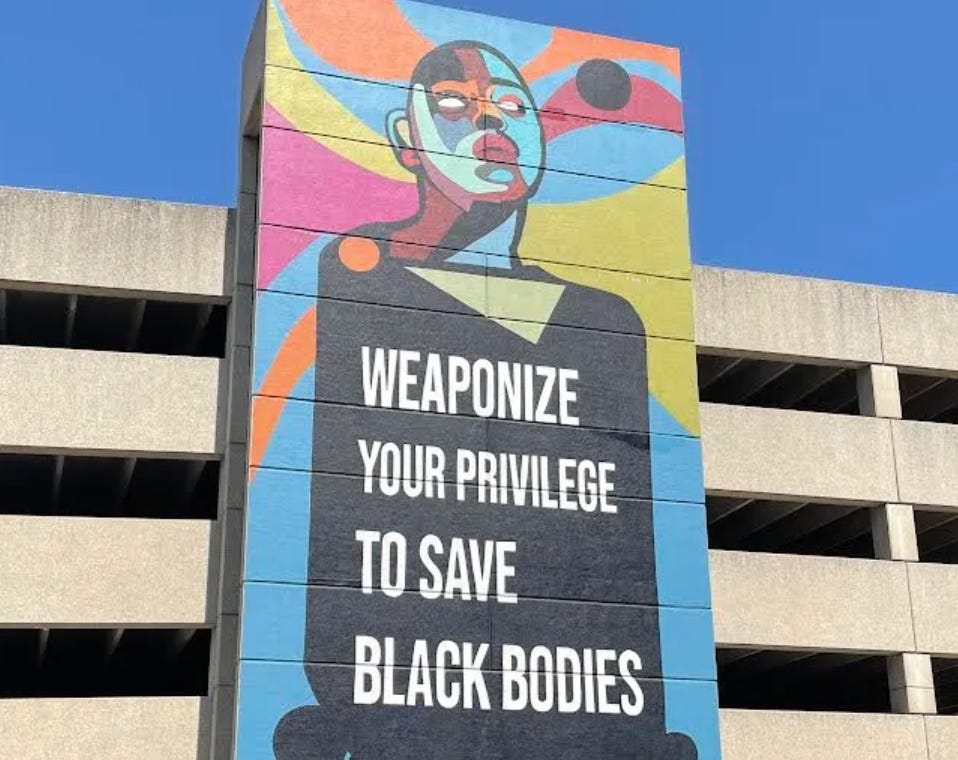

Later, Iowa City, also a college town but distinctly more hayseed rural than Lawrence, and home to the Iowa Writer’s Workshop. It feels like frat boy heaven, except the handful of Emotionally Disturbed Persons roaming the streets, who I can’t imagine have been there for long. And then, in the center of town, I see this:

And I would say that anyone who thinks these murals, appearing not in Berkeley or Seattle but in the middle of downtown Iowa City—the very definition of classic Americana—aren’t war propaganda misses the forest through the trees.

Being so shielded from war (perhaps the most shielded in human history), contemporary Americans have a poor understanding of it. Most of us believe “real wars”, meaning the Revolutionary War, the Civil War, WWI, WWII, appear suddenly, out of almost nowhere. Various atrocities occur, the bad guys lose, and the whole affair wraps up in a decade max. Our forays into both Vietnam and Afghanistan—neither of which we really consider war wars—only further demonstrate our notion that wars are more like spontaneous combustions than eroding cliffs. “And then one day, for no reason at all, people voted Hitler into power”—it’s a meme, sure, but it’s also an accurate portrait of what we learn in school. This is, of course, insane.

As any avid Dan Carlin listener knows, wars are less like unpredictable volcanic eruptions and more like bumps on an endlessly spinning wheel. What we refer to as “War”—three-to-seven year periods in which vast armies of men try to kill each other—are only the biggest, most jostling bumps. In fact, the wheel is always spinning, and always jostling. Big bumps are indeed coming as they always have and always will. War breaks in the sun til the sun breaks down.

An example. The first recorded violent confrontations in the conflict we call the Revolutionary War occurred more than 100 years before “The American Revolution” of 1775. More than likely, many smaller hot conflicts—perhaps resembling the recent occurrences in Oregon involving CHOP/CHAZ (on the left) or the Bundys (on the right)—happened years before that, but weren’t catastrophic enough to make the history books.

In 1676, Bacon’s Rebellion pit a ragtag alliance of frontiersmen and slaves against a 1,000 British soldiers. The colonists had claimed parts of Virginia territory reserved for Native Americans by the Crown. The natives kept attacking and killing the colonists, and the colonists sought total war against them. The Governor of Virginia refused to intervene, declaring that certain innocent Indian groups must be preserved, while rebel leader Nathanial Bacon wanted to “extirpate all Indians in general.”

“He was said to be about four or five and thirty years of age, indifferent tall but slender, black-hair'd and of an ominous, pensive, melancholly Aspect, of a pestilent and prevalent Logical discourse tending to atheisme... . He seduced the Vulgar and most ignorant people to believe (two thirds of each county being of that Sort) Soe that their whole hearts and hopes were set now upon Bacon. Next he charges the Governour as negligent and wicked, treacherous and incapable, the Lawes and Taxes as unjust and oppressive and cryes up absolute necessity of redress. Thus Bacon encouraged the Tumult and as the unquiet crowd follow and adhere to him, he listeth them as they come in upon a large paper, writing their name circular wise, that their Ringleaders might not be found out. Having connur'd them into this circle, given them Brandy to wind up the charme, and enjoyned them by an oath to stick fast together and to him and the oath being administered, he went and infected New Kent County ripe for Rebellion.” - An oh-so-objective Report of the Royal Commission describing Nathaniel Bacon

During a standoff in Jamestown, Bacon died of dysentery. “In the fall, Bacon, aged twenty-nine, fell sick and died, because of, as a contemporary put it, ’swarmes of Vermyn that bred in his body.’” Fake news then, fake news now.

The rebellion died with Bacon, but the spark didn’t and it wouldn’t until Independence. In 1677, just a year after Bacon’s Rebellion and inspired by it, grassroots leader John Culpeper led another uprising against the Lords Proprietor of Carolina over maritime customs duties called The Navigation Acts. The largely non-violent insurrection lasted two years, and Culpeper and his men managed to imprison the local customs director and briefly install their own government. Culpeper was tried for rebellion, but ultimately acquitted and sent home, in part because the Lords Proprietor didn’t want to encourage more resistance.

Bacon’s and Culpeper’s Rebellions, relatively large hot conflicts, predated the Big War, what we think of as The Revolutionary War, by a century. Following them, there were a thousand other flare ups including the Stamp Act Revolt and The Boston Tea Party, small bumps leading to the big show. The myopia of history makes us think that the Revolutionary War lasted 8 years. Really it lasted hundreds.

In America, we’ve already witnessed the first skirmishes in a war that will last for centuries. We will be defined by this war, just as those living in the 1700s were defined by theirs, but it won’t reach its Big War climax in our lifetimes. The 1600s and 1700s saw colonists versus an empire, but it took awhile to understand the larger pattern—the wider anti-monarchal struggle that also included the French Revolution only ten years later. We’re only just becoming aware of the sides in the central conflict of the Twenty First (and probably Twenty Second and Twenty Third Centuries): nationalists versus globalists.

Maps like the one below showing globalist-controlled areas (e.g. the Biden or Trudeau administrations) versus nationalist-controlled areas (the Trump or Bolsonaro administrations) will proliferate for hundreds of years to come. My intention with this piece and “There’s Gonna Be a War in Montana,” is merely to understand the depths of this conflict, and how it affects the ordinary people living through it.

A recent trend in movie posters features two sides—usually one blue and one red or yellow—opposing each other. You see this in all genres, not just the movies about humans v. zombies or Kong v. Godzilla. The trend is both a reflection and instigator of an American gyre that's widened far further than anyone living can remember. Musk himself tweeted "War is the Ultimate Supreme Court...," a late realization of what the Founding Fathers meant by "An Appeal to Heaven." War has crept into our consciousness and it's not leaving until we get it.

Yet the fearful or unimaginative say, “there can’t be war because there’s no battle lines! No Mason Dixon for armies to grow and gather strength behind!” Here in the age of decentralization we have not one Mason Dixon, but hundreds. A decentralized Mason Dixon that runs through Montana, between Bozeman and Three Forks. In Missouri, between St. Louis and Clinton. Behind it, the opposing sides in the first Big War of the Age of Aquarius are only just now rising from the primordial ooze.

War impossible? It’s already here. What were Waco, Ruby Ridge, Oklahoma City, CHAZ/CHOP, the BLM Riots, the Bundy standoff if not early skirmishes between nationalists (always called racists by the globalists) and globalists (always called communists by the nationalists)? Precursors to precursors of our generations’ Bacon’s Rebellion? We can't stop talking about war, thinking about it, making posters about it, because it’s already begun. We’re just figuring out what it looks like.

In June, thirty-one Patriot Front members were arrested in a U-Haul full of riot gear (no guns) apparently headed to a Pride Rally in Couer d’Alene, Idaho. The men had traveled from 10 states. Leader Thomas Ryan Rousseau was among those charged with conspiracy to riot, a misdemeanor. They were captured after a “tipster” reported seeing people loading up in a U-Haul. They “looked like a little army,” he said.

You are opening up my mind to things I really don't want to think about, but I know in my heart that that's a good thing! I cannot get the thought of my head though that there are entities involved in all of this, beyond our understanding, spiritual forces influencing the thoughts and actions of people, some willing some not. We just need to make sure we're on the right side because it doesn't end well for the wrong side. Anyways, thank you for sharing your wisdom and please, keep it up!

the civil war was city whites (globalists) vs country whites (nationalists). plus ca change. or whatever that french guy said.