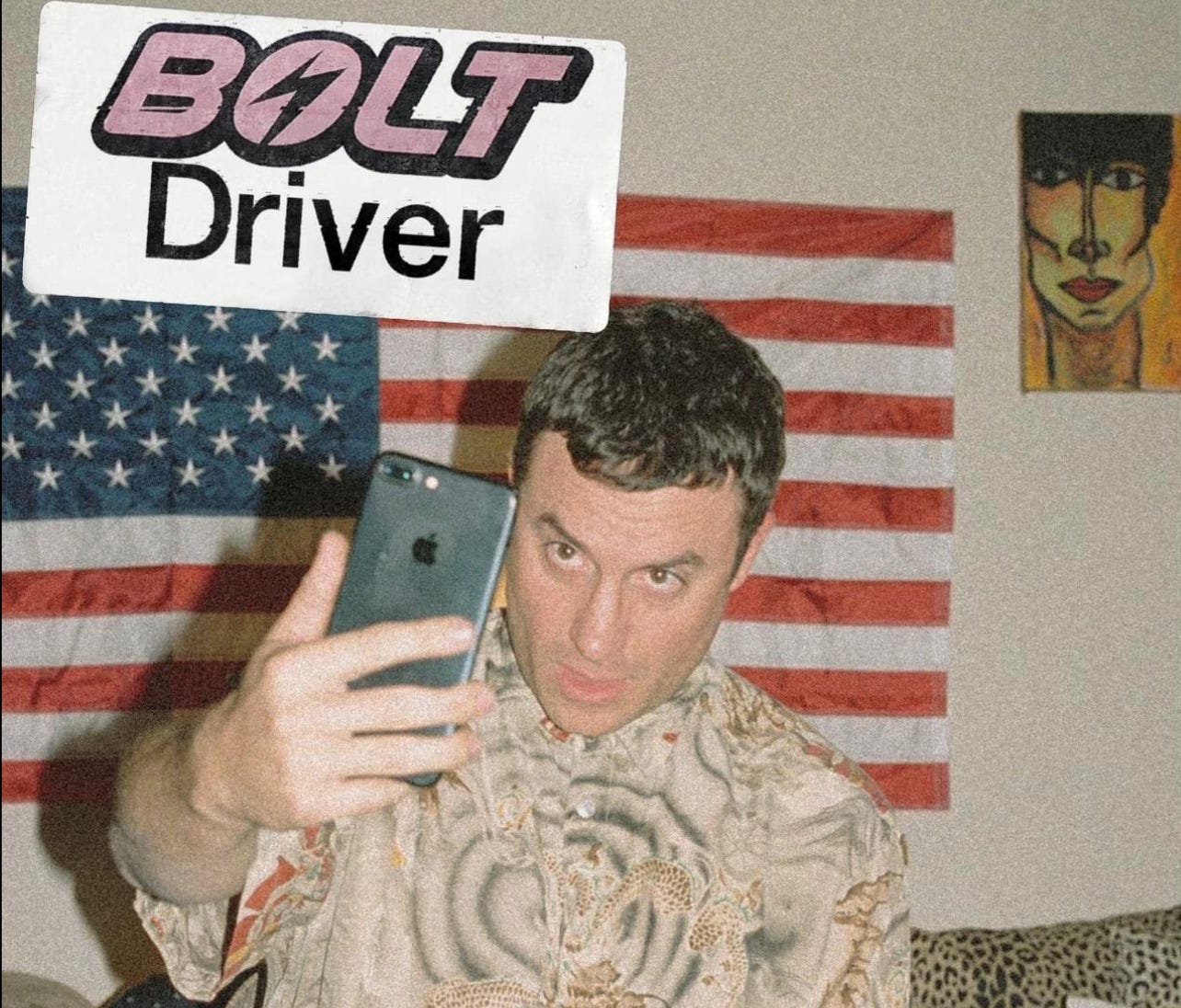

The canary in the coal mine, as they say, of this world collapsing and forcing me to display my genius was the Hooters of Burbank and Hooters of Hollywood closing for good thanks to PC culture and this Bidenocracy. I wish to thank everyone who helped shape my genius from the doomers, and druggiies in my B0lt to the onlyfans girls who ji[pped me all those times, they were MY wanda and now I present my VISION: enjoy. --Boltdiver.LA

Boltdriver is a movie. You can watch it for free on Boltdriver.la, and, as far as I know, nowhere else (and why would you…it's free). There’s little else to explain what Boltdriver is. The website is minimal. There are no credits, much less bios of the filmmakers. It has no synopsis, no trailer, no reviews, no links. It's just Bolt Driver. Press play.

Below the play button is an anonymous typo-ridden, free-associated farewell statement, the kind left from beyond the grave after a suicidal blaze of glory, or maybe just when a barely-followed meme page shuts down. It’s signed “Sent from my Iphone”. A couple intriguing stills, and a copyright. Even Bolt driver’s running time evades easy explanation; at 40 minutes, it’s exactly the wrong length for anything—too long for short showcases, too short to be sold as a feature.

Starting the movie with virtually no context, all you have to go on is the title, and the title “Bolt Driver” feels loaded. It evokes the lethal mechanics of a gun, and as funny, pathetic, weird and strange as the film is along the way, the title keeps your lizard brain braced for a doomed and bloody ending. It’s literal too: “Bolt” is the name of the Estonian-based Uber competitor our anti-hero rides for. He is a driver, and he drives for Bolt. It exists only on the internet, only for the internet. Nay, it seems to be from the internet, emerging sui generis.

Of course, someone made it. Made it well. It’s co-directed by an award-winning music video director Van Alpert and its star, Nick Corirosi, but their presence isn’t foregrounded. There’s an artistic oomph to this hint of anonymity, not just for the freedom it offers, but the poetic mysteriousness it lends. Delicious Tacos, Bronze Age Pervert, and for some schizoid freaks these days even Shakespeare, all benefit from a foggy mist blurring out the face of their authors in our minds' eyes (imagine if DT’s stories were written by a Travis Walton or, god forbid, a Pete Monte…yawn).

Looking at Corrorosi’s other works, he seems aware of this. One of his side projects is Bug Mane, a Daft-Punk style faceless, uncredited musical alter ego. And the only findable interview he’s done about Bolt Driver was a zoom Q&A he did with students from the University of Central Florida, in which he refused to break character (“I heard you guys are watching this thing about when I was driving those people around in Bolt car”).

As the plot unfurls, another meaning emerges. “Bolt Driver” it’s also a referential title, a soft rhyme with Scorsese’s “Taxi Driver”, the film it “paraphrases”. A “paraphrase film” is a neat new genre coinage Tarantino concocted in his recent auto-bio/stab at film criticism, Cinema Speculation. De Palma’s Dressed to Kill, for example, is not a remake of Psycho, but exists entirely in reference to it; viewers who’ve seen both enjoy an added layer of allusions and variations, mirrors and rhymes.

Bolt Driver’s main premise—Taxi Driver-as-incel—has such an elegant modernization math (the kind of idea that is instantly obviously right) that its inspired a veritable mini-genre of similar paraphrases. There’s Joker, wrongly derided as a mere ripoff. Then there’s Eugene Koltlyranko’s cult horror flick Spree, who’s near simultaneous creation to Bolt Driver makes it, if not a paraphrase film, than at least a parallel one (Spree was also shot on Iphones, and Bolt Driver’s star and co-director even appears in Kotlayenko’s previous film Wobble Palace shot just afterwards in 2017). Clearly, Taxi Driver is having a moment.

Bolt Driver is the cheapest, the most misshapen, the grimiest of these films. Zero-budgeted, it’s a hodgepodge of uncleared music and stolen shots, sliced together with the cheap home editing effects and gusto of a whizbang youtuber. The whisper of a plot is updated to 2016, from taxi to rideshare. Instead of Cybril Shepherd’s angelic campaign volunteer, our anti-heroic stalker’s eye fixates on a sexy little Trumpette he drops off at the election office (Margaret Qualley’s sister, Rainey). I say whisper, because little time is spent on plot. Most of Bolt Driver is just a running voiceover commentary by our friendless, only fans-addicted driver as he wanders a hellscape version of LA. The lightweight iPhone camera following him is always in motion, capturing shots of homeless men smoking cigarettes as they stroll by apocalyptic fires, or candid footage from an adult video convention our demented protagonist crashes with his first paycheck.

This running monologue is actually a paraphrase of a paraphrase, echoing the source material within the source material, as Taxi Driver was itself inspired by the unreliably narrating, endlessly shpieling protagonist of Dostoeyvsky’s Notes From Underground. Bolt Driver’s effectiveness is built around this gruesomely comic performance by Cororosi, who uncannily channels his creation with the Seroquel-slurred speech impediments of someone whose antipsychotic medication is only mostly working. His facial expressions seem incomplete, with bugged eyes that rarely match his face–everything he says sounds like a guess at what a normal person would say. Trying to pick up girls, his affect is kryptonite to human attraction, with the added curse of never understanding why people are so repulsed. He imagines himself a hero; he sees Bolt‘s “pussy pink”-colored lightning strike logo emblazoned on the hood (like the Lyft mustache) as a Shazam-like design that turns his car into a superhero’s vehicle, like the Batmobile.

Paul Schrader’s original script for Taxi Driver was written from a place of suicidal despair, the itinerant vehicle an image of isolation. It’s metaphor is astute. After a series of mid-life catastrophes, I had to drive an Uber to survive—and Schrader was right. If you’re already depressed, freelance transport gigs are torturously close to socializing, without actually delivering the goods. You can’t take phone calls, or listen to books or radio shows. Beyond functionalities, you cannot talk, really talk, to the customers. But you can find yourself listening in on their world, ever eavesdropping on the lives of others who seem to have places to go.

And when we spend our alone time online, like the driver, we can't spend it in reflection or meditation. We cannot go inward. But we cannot go outward either; our faces are pressed outside against the window of a party we can never enter. Asymmetrically tracking strangers' lives, we constantly tongue the wound of our own isolation.

Underground men have always existed. The taunting mockery of connection that haunts Bolt Driver—a “personal message” from an only fans girl, a one-sided follow that will never be mutual—exaggerates a phenomena experienced by rejects of the past. These overwritten and under-read posts into the abyss may feel peculiarly modern, but involuntary hermits and social rejects have always kept madmen’s diaries. Reading Notes From Underground you will find the same echo chamber, the ultimate echo chamber: a man’s mind. That is eternal.

But, by building Bolt Driver’s obscurity as a human, into the obscurity of the films aesthetic, it captures something more unique to our time. That’s why I preferred discovering this film from a recommended link to a crude website. Today’s notes from underground are no longer hidden away in attics or floorboards. Now, voyeuristically, we can just read the ephemeral greentexts on faceless message boards, or peruse the no-view count videos of schizophrenics crying out from their cells. Because insane asylums now all have glass walls. The inmates stare out at us through distorted viewpoints, but we can look back.

All we have to do is watch.

I just finished the movie. I re-watched Taxi Driver since there are some shot for shot touch-points with the mailbox and diner scenes. There isn't anything in particular that drives our main character the Bolt Driver crazy. More of a slow descent into evermore danger, confusion and with no mother or father to call upon. For they are just as lost somewhere in the ether of the streets.