The Swoosh never meant to “change the world,” even by the most generous definition of that insipid phrase. It was a rushed, practical decision. A box checked. This is how most iconic brands are born.

Nike launched in 1964 as an Onitsuka running shoe importer named Blue Ribbon Sports. In 1971, founder Phil Knight fell out with the Japanese, and decided to develop his own line. He asked Carolyn Davidson, an artist acquaintance from Portland State, to sketch a few logo ideas based on “the concept of motion.” That was the entire brief.

Here’s how Knight describes what happened next (from his autobiography Shoe Dog):

“Her designs did evoke motion, of a kind, but also motion sickness. None spoke to me. I singled out a few that held out some promise and asked her to work with those. Days later—or was it weeks?—Carolyn returned and spread a series of sketches across the conference table…these were better….Gradually we inched toward consensus. We liked…this one…slightly more than the others. It looks like a wing, one of us said. It looks like a whoosh of air, another said…We all agreed it looked new, fresh, and yet somehow—ancient. Timeless. For her many hours of work, we gave Carolyn our deepest thanks and a check for thirty-five dollars, then sent her on her way.”

Is this really the entire story of the most iconic brand in corporate branding history? Actually no, there’s a bit more.

“After she left we continued to sit and stare at this one logo, which we’d sort of selected, and sort of settled on by default… ‘You guys like it more than I do,” I said. “But we’re out of time. It’ll have to do…I don’t love it, maybe it will grow on me. We sent it to Canada.”

That’s it. That’s how the Swoosh came to be.

Less hilarious, but equally absurd, is the story of the name Nike, which came just after the Swoosh. The day before the decision needed to be made, “Nike” wasn’t even in the running. The finalists were Falcon and Dimension Six, with Bengal a distant third. Phil Knight loved Dimension Six, but everyone else on his team hated it. According to Knight:

“Finally, we needed to file paperwork with the U.S. Patent Office. Woodell wheeled into my office.

“Time’s up,” he said.

I rubbed my eyes. “I know.”

“What’s it going to be?”

“I don’t know.”

My head was splitting. By now the names had all run together into one mind-melting glob. Falconbengaldimensionsix.

“There is…one more suggestion,” Woodell said.

“From who?”

“Johnson [Blue Ribbon Sports’ head sales guy] phoned first thing this morning. Apparently a new name came to him in a dream last night.”…

“What is it?"

“Nike.”

“Huh?”

“Nike.”

“Spell it.”

“N-I-K-E,” Woodell said.

I wrote it on a yellow legal pad. The Greek goddess of victory. The Acropolis. The Parthenon. The Temple. I thought back. Briefly. Fleetingly.

“We’re out of time,” I said. “Nike. Falcon. Or Dimension Six.”

“Everyone hates Dimension Six.”

“Everyone but me.”

He frowned. “It’s your call.”…

I hated making decisions in a hurry…I gave myself two more minutes to mull over the options, then walked down the hall to the telex machine. I sat before it, gave myself three more minutes…A lot of things were rolling around in my head…seemingly all iconic brands—Clorox, Kleenex, Xerox—have short names. Two syllables or less. And they always have a strong sound in the name, a letter like a “K” or “X",” that sticks in the mind…Also, I liked that Nike was the goddess of victory…in the end I don’t really know what led me to my decision. Luck? Instinct? Some inner spirit.

“Nike,” I mumbled. “Hm,” he said. “Yeah, I know,” I said. “Maybe it’ll grow on us.”

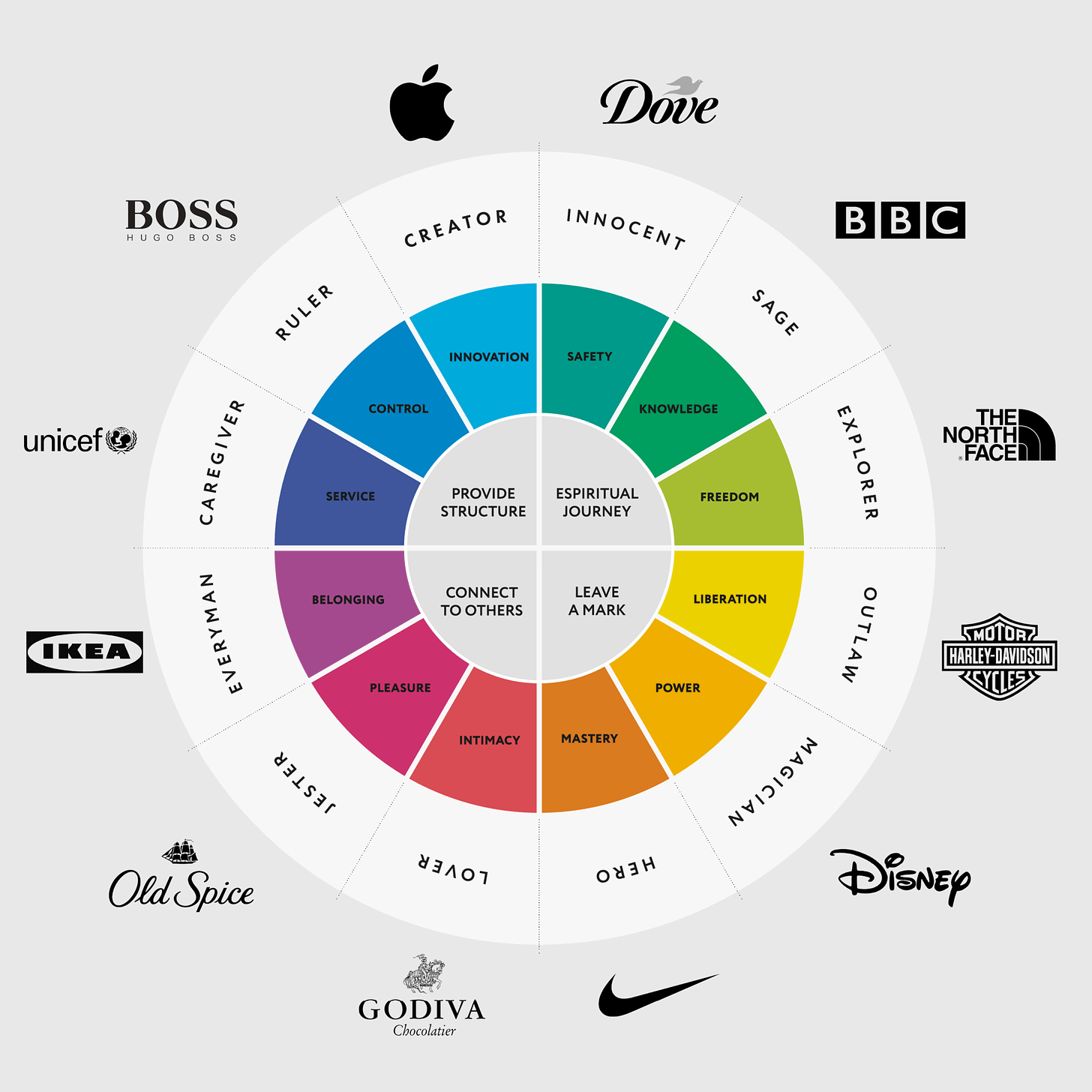

I can’t think of a great brand (logo or name) hatched from the masturbatory WeWorkshopping that’s become the norm today. This reality runs counter to our Hype Dad marketing regime, which treats branding more like Jungian psychotherapy—“Who am I really?”—than a business decision.

Knight was an accountant, and he made creative decisions like one. Pragmatic. Efficient. Pros and cons, business angles, a little bit of gut instinct. Very little fanfare or navel gazing. No manifestos. No therapy sessions. That’s why he was so good at it. Maybe the best.

I know what you’re thinking. Surely other brands were meant to change the world, then did so! What about McDonald’s? What about Steve Jobs??

In the instances of Apple and McDonald’s, visionary entrepreneurs created their own brands from scratch. Their legends have grown, but they were pretty basic business decisions at the time.

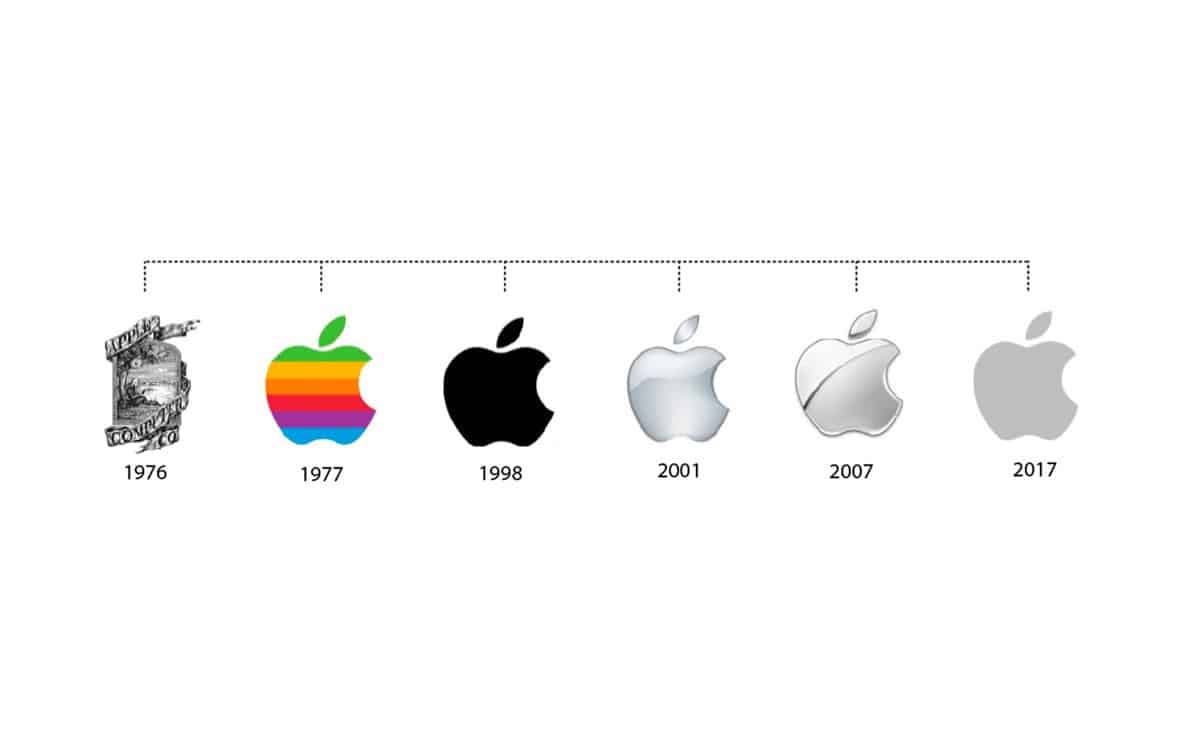

When Apple first started, Isaac Newton was an inspiration. So co-founder Ronald Wayne made a silly logo featuring Newton under a tree in a realist landscape. Jobs of course wasn’t having it, so he hired graphic designer Rob Janoff to make something easier to replicate, and that would simply communicate “the first color computer.” Jobs never said much more about it, besides that he chose green for the top of the apple because “that’s where the stem is.”

As for the name Apple, the story is equally banal—basically Jobs visited a cool apple orchard—and had nothing to do with Alan Turing, despite the myths.

McDonald’s followed a similar pattern, with Ray Kroc playing Jobs. Kroc’s inspiration was the architecture of the restaurant itself, which was built before Kroc’s time. The Golden Arches don’t “mean” anything. They were just an eye-catching structural element, built to be noticeable and nothing more.

The Swoosh. The apple. The Golden Arches. All achieved by small teams without an agency and without really knowing what they meant, besides that they looked cool and were easy to replicate.

Founders today want brands that mean as much as the Swoosh, so they hire agencies to create 100 page decks full of brand strategy, market research, social listening, competitive analyses, customer personas, mood boards, and manifestos that explain why their new brand is actually a vector to utopia. Is it branding or is it the Zodiac?

I’m not challenging the power of brands themselves—quite the contrary. Branding decisions have indeed sparked revolutions, the arches and the apple included. The hammer and sickle, the swastika, the American Flag are all brands in their own right.

But even these were vague ideas from random places, refined to simpler symbols. Good brand work is absolutely vital, but good brand work is about developing and expressing the brand, not dwelling on how important it is.

Hype Dads convince companies left and right to transcend brandhood and become the most coveted of all Hype Dad identities, “World Changer,” if only they spend 300k on brand guidelines. But it’s just not going to happen that way.

Because the brands that mean the most aren’t built with meaning in mind.

Next Week: Ok Mr. Negative, then how should we go about branding?